|

|

|

| Swammerdam’s science His life and work Nerve function Muscles Bees and ants "The Bible of Nature" Amazing drawings Techniques and microscopy Preformationism Swammerdam’s life Birth Death A fake “portrait” Science in society Empiricism and religion Mysticism and modern science Illustrations and their meaning Swammerdam in culture Swammerdam's world Friends and contemporaries Contemporary accounts On-line resources Under construction: Discussions of Swammerdam’s work A bibliography of Swammerdam's works Contact |

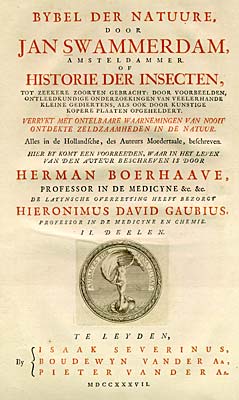

From 1676 until his death he worked incessantly, rewriting his previously-published material and carrying out new research. For example, he extended the material on ants from half a page in the Historia Insectorum Generalis to over 12 pages in The Bible of Nature. He also wrote a series of scientific letters to Thévenot, subsequently included as whole new sections, such as his astonishing description of the behaviour, anatomy and metamorphosis of the cheese skipper fly and its larva. By the end of 1679, the manuscript was complete and the illustrations were virtually finished; two plates had been cut and the translation from Dutch to Latin was underway. However, Swammerdam’s health took a turn for the worse as his malaria returned. After a final debilitating fever, he died on 17 February 1680, leaving his papers to his great friend Thévenot, with the request that he publish them. Thévenot was not able to meet Swammerdam’s dying wishes. First, the translator refused to release the manuscript. After a two year law-suit, Thévenot eventually acquired the papers but he died before he could prepare them for the press.  Part of the Catalogue of Thévenot's library referring to Swammerdam's manuscripts. On Thévenot’s death his papers were sold and the manuscript was bought by the King’s painter, Joubert. On Joubert’s death it was sold again. The great Dutch physician Herman Boerhaave (1668-1738) eventually learned of the existence of the papers and managed to buy them in 1727, just as a swindler was trying to pass them off as his own. Like Thévenot, Boerhaave found that preparing the papers for publication was more difficult than at first appeared. He had to reduce the section on the may-fly by cutting “all the pious meditations and religious sentiments with which the original is so liberally furnished” (320 pages out of 430!). He also had to track down some missing material from the treatise on bees and decide where to insert the scientific letters to Thévenot. The remaining 16 of the 52 plates planned by Swammerdam had to be engraved, together with an extra plate, depicting the sporangia of ferns. Ten years after Boerhaave acquired the papers, the Bybel der Natuure (“The Bible of Nature”) was published in Dutch. Boerhaave took the title from one of Swammerdam’s letters to Thévenot:  The Dutch text was accompanied by a Latin translation and 53 plates, in two handsome folio volumes (1737 and 1738). The first volume, complete with a biographical introduction by Boerhaave which still forms the basis of our knowledge of Swammerdam’s life, marked the centenary of Swammerdam’s birth. Nearly 60 years after the work was completed, the second volume appeared as Boerhaave lay on his death-bed.  This illustration was taken from here. The scientific ambition represented by The Bible of Nature is astonishing. Even today it shocks by its audacity. In its scope and depth, Swammerdam’s work far exceeded any other book of the time. Although laying the basis for much of modern biology (in particular entomology), The Bible of Nature is clearly very much of its time. It is full of charming pre-modern digressions, such as a tall tale of a maidservant trying to thread woodlice thinking they were pearls, a useful description of how to go fishing using cormorants or an ingenious technique for engraving pictures on snail shells. A German translation appeared in 1752 (Bibel der Natur), followed by an English translation in 1758, under the mis-translated title "The Book of Nature", by which it is generally known today. A slightly reduced facsimile of the English edition was produced in 1978 by Arno Press. It is still available. Click here for more details. In 1980 a two-volume facsimile of the Dutch edition was produced. It is out of print, but still turns up on second-hand bookshop websites. This page is partly excerpted and adapted from an article that appeared in Endeavour (2000) 24(3) pp122-128. © Elsevier Science, 2000. To download a PDF version of the full article, click here. |