|

|

|

|

Swammerdam’s science

His life and work Nerve function Muscles Bees and ants "The Bible of Nature" Amazing drawings Techniques and microscopy Preformationism Swammerdam’s life Birth Death A fake “portrait” Science in society Empiricism and religion Mysticism and modern science Illustrations and their meaning Swammerdam in culture Swammerdam's world Friends and contemporaries Contemporary accounts On-line resources Under construction: Discussions of Swammerdam’s work A bibliography of Swammerdam's works Contact |

In 1860, the German writer Klenke produced a three-volume novel about Swammerdam's life, called "Johannes Swammerdam". There are copies in the British Library and in the University Library at Leiden. In the 1941 German novelist Olga Pöhlmann published a "biographical novel" on Swammerdam, complete with a number of illustrations from Swammerdam's work and an introduction by Swammerdam's biographer, Shcierbeek (written in 1938). In 1944 Pöhlmann's book was translated into Dutch and Swedish, and later went into a second (retitled) German edition in 1957. The original German edition and the Dutch translation both used (poor) reproductions of Rembrandt's work to illustrate the period.

In 1946, presumably inspired by both Pöhlmann and by Schierbeek's biography, Manuel van Loggem, who was to go on to be a major Dutch science fiction writer, produced his novelised version of Swammerdam's life, "Het Kleine Heelal":

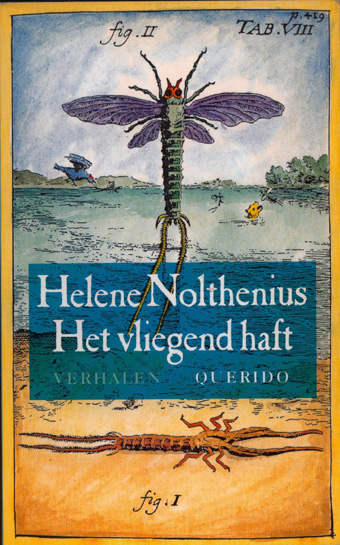

More recently, in 1993 Dutch novelist Helene Nolthenius devoted the title story of her colleciton of short stories "Het vliegend haft" to Swammerdam ("haft" is the Dutch word for mayfly). The cover incorporates a coloured version of a drawing by Swammerdam of mayflies dancing over water that originally appeared in Historia Insectorum Generalis (1669) and, in slgihtly altered form in the Bible of Nature:

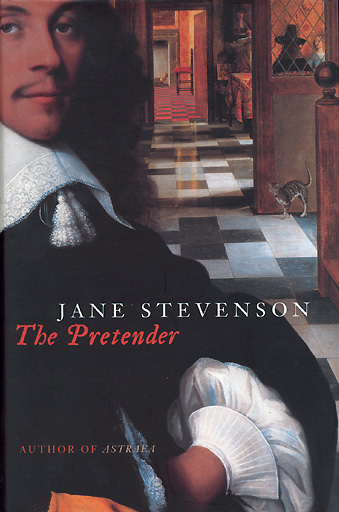

Swammerdam has had a minor role in two recent British novels. He is the subject of a pastiche 19th century romantic poem in A. S. Byatt's 1990 novel "Possession" (to be found at the beginning of Chapter 11). He also appears at the beginning of Jane Stevenson's 2002 novel "The Pretender", which is partly set in the 17th century Netherlands. The figure on the cover is "A gentleman" by Palamedesz, set against an interior by van Hoogstraeten:

|