|

|

|

| Swammerdam’s science His life and work Nerve function Muscles Bees and ants "The Bible of Nature" Amazing drawings Techniques and microscopy Preformationism Swammerdam’s life Birth Death A fake “portrait” Science in society Empiricism and religion Mysticism and modern science Illustrations and their meaning Swammerdam in culture Swammerdam's world Friends and contemporaries Contemporary accounts On-line resources Under construction: Discussions of Swammerdam’s work A bibliography of Swammerdam's works Contact |

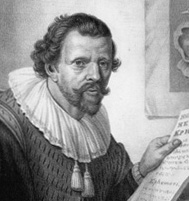

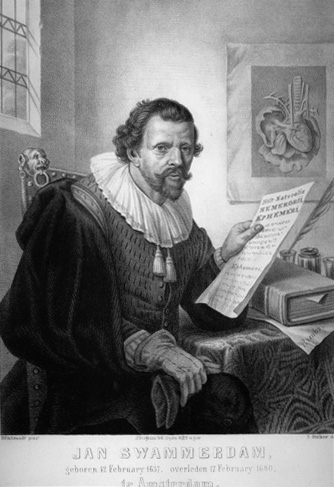

No known portrait of Swammerdam exists. However, an alleged portrait of him still resurfaces occasionally. The (rather poor) lithograph reproduced here was made by Berghaus in 1851 (a similar lithograph was made around the same time by Lankhaut). According to the caption, the engraving is taken from a drawing by Jan Stolker (1724-1785) a minor Dutch artist of little talent, which in turn was made from a painting by Rembrandt.  © M. Cobb A more stylised woodcut was made by Giacomelli to accompany the 1875 edition of Jules Michelet’s "L’Insecte" (thi s is the image used on each page of this site).  © Bibliothèque centrale MNHN, Paris. Perhaps the portrait is genuine? After all, Swammerdam and Rembrandt lived in Amsterdam at the same time and, according to one story, Swammerdam treated the artist’s poorly son, Titus. The truth is complicated: Rembrandt both was and was not the author of this “portrait” of Swammerdam. He was not the author because the portrait allegedly shows Swammerdam with a copy of his book on the may-fly, Ephemeri vita. The book was published in 1675, whereas Rembrandt died in 1669. He was the author, in a way, because the face in the portrait of Swammerdam has clearly been taken from Rembrandt’s masterpiece “The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Tulp”:  © Mauritshuis, The Hague The figure in the hat on the right is Nicolas Tulp. Look at the person next to him, staring at the viewer.

This is obviously the original source for the "Swammerdam" portrait. Could it in fact be Swammerdam? No. Although Nicolas Tulp was head of the Leiden medical school where Swammerdam studied, he retired from teaching before Swammerdam arrived, so it is unlikely that Swammerdam actually assisted at one of Tulp’s dissections, although they did know each other. More decisively, Rembrandt painted the picture in 1632, five years before Swammerdam was born! In 1876 the face was identified as that of Hartmann Hartmanzoon (1591-1659), a leading member of the Amsterdam medical community. Despite this, the portrait is regularly reproduced in both print and on the web as being of Swammerdam. It seems most likely that the original “portrait”, the whereabouts of which are unknown but which was obviously in circulation in the mid-19th century, was concocted — not necessarily with malicious intent — by Jan Stolker, who apparently had a “talent for creating new compositions with elements taken from older models”. Two other openly imaginary "portraits" exist:

This charmingly inaccurate image (a duotone litho by Emrik & Binger from a series of 'famous Dutch persons') has Swammerdam wearing 18th century clothes, sitting in what looks to be an 18th century chair and using a compound microscope... By the 20th century, the popular image of Swammerdam had changed, and in 1944 the Amsterdam sculptor Dirk Dik Stins (1914 — ca.1989) made the following imaginary bust of an extremely dour-looking Swammerdam, which clearly owes its inspiration to the 17th century (and far more cheerful) bust of Swammerdam's friend and colleague, Ruysch (click here).

The bust, which is around 40cm high, can be found in the Artis library of the University of Amsterdam (accession number 000-403). References: Harting, P. (1876) ‘Johannes Swammerdam. Een Levensschets’, Album der Natuur:1-28 te Rijdt, R.J.A. (1990) ‘Een uitnemend geordonnerde en geteekende titel’ door Jan Stolker, Delineavit et Sculpsit 6, 28-33 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||