|

|

|

| Swammerdam’s science His life and work Nerve function Muscles Bees and ants "The Bible of Nature" Amazing drawings Techniques and microscopy Preformationism Swammerdam’s life Birth Death A fake “portrait” Science in society Empiricism and religion Mysticism and modern science Illustrations and their meaning Swammerdam in culture Swammerdam's world Friends and contemporaries Contemporary accounts On-line resources Under construction: Discussions of Swammerdam’s work A bibliography of Swammerdam's works Contact |

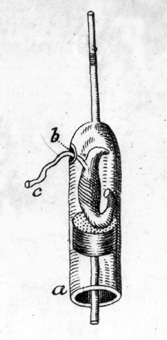

To test Descartes’ hypothesis that the influx of “animal spirits” increased muscle volume on contraction, Swammerdam placed a frog muscle in an air-tight syringe, and measured the volume of the muscle in its contracted and relaxed state by observing the movement of a bubble of water in the end of the syringe. Swammerdam first did the experiment with a whole frog heart that had been dissected out:  The result was incontrovertible: when the heart spontaneously contracted “the drop of water adhering near the extremity of the tube, c, descends in a very remarkable and surprizing manner (...) the drop thus fallen down, d, will, on the heart’s dilating itself again, rise to its former situation, c.” This completely contradicted Descartes’ hypothesis. He then slightly altered the procedure, using a frog’s thigh muscle, with the nerve protruding through a small hole in the side of the glass siphon:  The results were disappointing: “In this experiment, the sinking of the drop is so inconsiderable, that it can scarce be perceived”. Most scientists will recognize his next, fatal, step. Swammerdam explained away the results from the thigh muscle experiment, arguing that “this experiment is very difficulty sensible, and requires so many conditions to be exactly performed, that it must be tedious to make it” and pointing out that because the thigh muscle had neither blood supply nor antagonistic attached to it, it could not be expected to function normally, concluding “for this reason, the heart is fitter for this experiment than any other muscle”. But in fact, the thigh muscle preparation gave the right result. Muscles do not change their volume. Although he can be commended for not hiding difficult results, Swammerdam was wrong. Convinced that the big effect was what counted, he dismissed the thigh muscle results. His mistake came because when the heart contracted it probably compressed some of the air trapped in the ventricles, reducing the total volume in the syringe. Swammerdam decisively proved Descartes wrong, but unwittingly he provided modern scientists with a salient lesson in how to interpret experiments and the need to exclude artefacts. This page is excerpted and adapted from an article published in Nature Reviews: Neuroscience, May 2002, Vol 3, pp395-400. To download the full article, in PDF format, click here. The Nature Reviews: Neuroscience website can be found here. |